On the Road – Ventoux – Distance: 123km I 76 miles I Elevation: 2366m I 7762ft

Today we headed north towards the Alps. After a coffee in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, where we grabbed some bottles for a later tasting…. our route skirted the ‘Giant of Provence’, otherwise known as Mont Ventoux. Whilst we don’t imagine that Hannibal went looking for extra climbing, we couldn’t pass by this cycling mecca without the chance to climb it. We took on the classic Tour de France climb from Bedoin and descending into Malaucene. The day’s weather was almost perfect although it did get to 36C. (When I rode up Ventoux six years ago it was foggy, rainy and cold). Our destination was the pleasant market town of Nyons which places us perfectly for our Alpine assault.

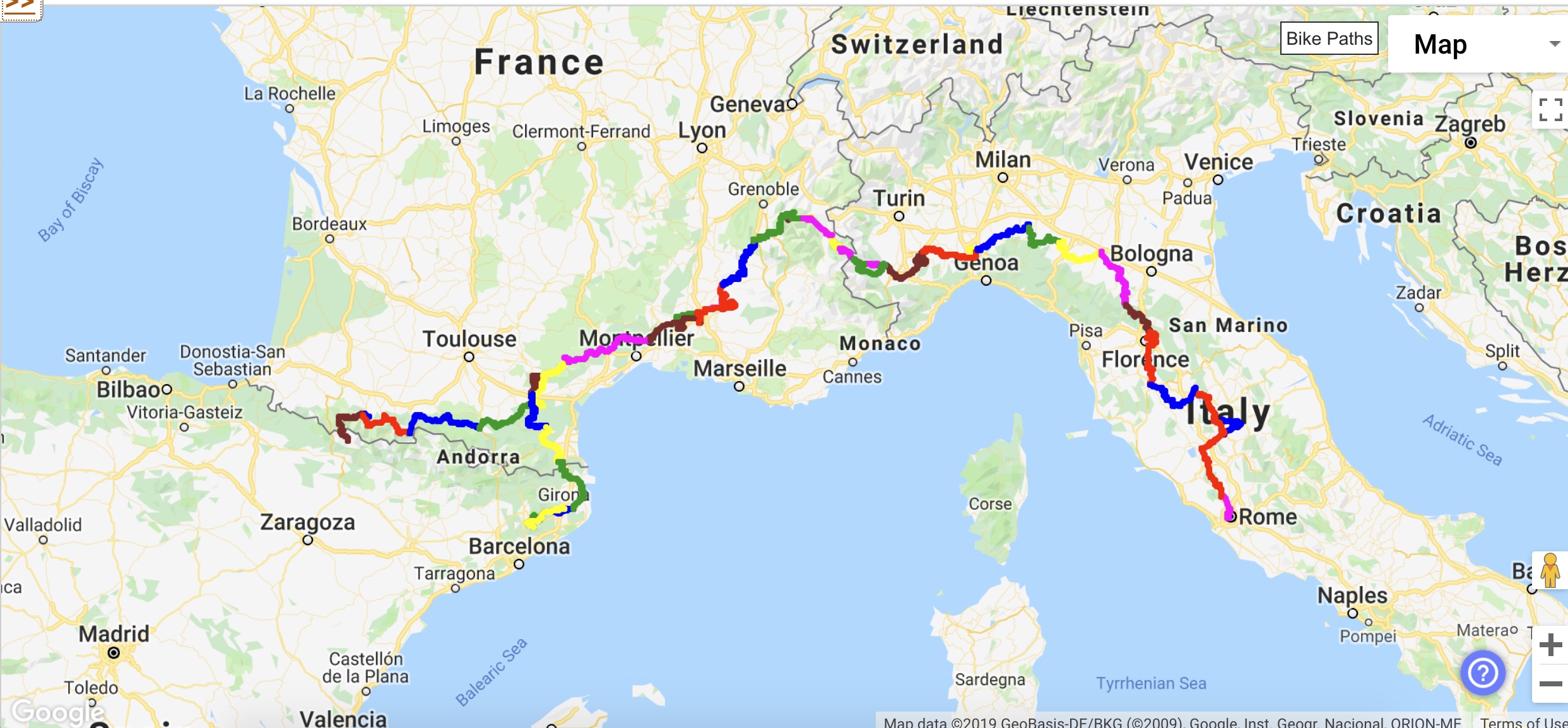

https://www.relive.cc/view/rt10008074630

Field Notes: Ventoux and Tour de France

The Tour de France first ascended Mt Ventoux in 1951 (when it came from the Malaucène side) but wasn’t used as a hilltop finish until 1958 in stage 18. Unsurprisingly, eventual 1958 Tour de France overall winner Charly Gaul won the stage.

Mont Ventoux etched itself into cycling history when British rider Tom Simpson died near the top in the 1967 Tour de France. His death was attributed to a combination of dehydration from the day’s extraordinary hea

t, a case of diarrhea, lack of available water, amphetamines and alcohol. Near the top there is a memorial to Tom Simpson.

Eddy Merckx didn’t think racing up Mont Ventoux in the 1970 Tour would be anything special, but he was in such rough shape after winning the stage he was given oxygen.

Marco Pantani broke away on Mont Ventoux in stage 12 of the 2000 Tour de France. Armstrong bridged to the Italian and then eased slightly to let Pantani take the stage. This is the usual practice among professionals. The GC contender, content with the time gain, lets his fellow breakaway rider take the stage. But Armstrong, in an ill-mannered move, told the press he had let Pantani win. Pantani, always insecure, was humiliated and several times launched suicidal attacks in the mountains, aimed at Armstrong.

In the 2013 Tour, after four rated climbs, the top of Mont Ventoux was the finish of the year’s longest stage. Overall 2013 Tour winner Christopher Froome executed a dominating ride, confirming his status as the best rider in the race.

The fastest fifteen recorded times for a Mt. Ventoux ascent are all before the UCI’s imposition of the biological passport in 2008. The reader can draw his own conclusions. The fastest known ascent was by Iban Mayo in the 2004 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré. He did the Bédoin ascent in 55min 51sec. Charly Gaul’s 1958 time was 1hr 2min.

The climb is almost 22 kms at an average grade of 7.6%. It is challenging, epic and one of cycling’s best cols. and is why it is The Giant of Provence!

At 1,912m Mont Ventoux is the highest mountain in the region. As the name might suggest (venteux means windy in French), it can get windy at the summit, especially with the mistral; wind speeds as high as 320 km/h (200 mph) have been recorded. The real origins of the name are thought to trace back to the 1st or 2nd century AD, when it was named ‘Vintur’ after a Gaulish God of the summits, or ‘Ven-Top’, meaning “snowy peak” in the ancient Gallic language. The top of the mountain is bare limestone without vegetation or trees, which makes the mountain’s barren peak appear from a distance to be snow-capped all year round (its snow cover actually lasts from December to April).

Destination – Nyons

Nyons is a commune in the Drôme department which was settled in the 6th century BCE as Nyrax by a Gallic tribe, probably the Sequani. Hecataeus of Miletus mentioned Nyrax around 500 BCE when writing about the Celts. It is situated next to the river Aigues or Eygues, which is crossed by an ancient bridge. It is famed for its black olives today which have PDO status.

Hannibal and the Rhone

For Hannibal, crossing the Rhone was a huge obstacle. His crossing was opposed by the Volcae – an aggressive local Gallic tribe. Hannibal’s strategy was to send his nephew Hanno with a detachment of troops north. He was to cross the river upstream and surprise the Volcae.

Hannibal bought up all the local boats, canoes and anything that would get his huge army and baggage train across the fast flowing river. The Rhone is no longer a wild river – the only peril today seems to be massive transport barges which speed downstream. In Hannibal’s time it would have been a dangerous obstacle and he seemed to be very diligent in his preparations.

Once Hanno had sent a smoke signal to notify his uncle he was in position, Hannibal embarked with his main force. When he landed on the opposite bank Hanno sprung his ambush. The Volcae’s raucous howling turned to panic as they were caught in a classic pincer movement.

Once Hannibal had set up his beachhead on the east bank of the Rhone he began the extensive operation of getting the rest of his troops across the river. Smaller boats crossed in the lee of larger vessels so they didn’t bear the full brunt of the current. The cavalry swam with their rides but the elephants needed more persuasion.

Polybius says that Hannibal built rafts, covered them with soil and urged a female elephant onto these floating islands and the rest of the herd followed. However, once the rafts were detached from the bank, the elephants panicked and were forced to make their own way across to the other side – Polybius believes the elephants walked across the bottom of the river using their trunks as snorkels!

Livy, our other main ancient source, writes that the elephants swam from the beginning following the lead male, who was driven to a rage by his driver. This brave man then jumped into the river himself, with the elephant herd following the lead male who, in turn, was intent on catching the driver – who would have swum desperately fast to the other side!